Viper Energy Partners (NASD:VNOM) is a three-year-old Master Limited Partnership (MLP) that owns oil and gas royalties in the Permian Basin of West Texas. Backed by a strong shale oil exploration and production partner, Diamondback Energy (NASD:FANG), Viper possesses good visibility to increase its cash distributions 25-30% over the next two years while paying out a 7% distribution along the way as it continues to purchase more royalty stakes from its general partner and third parties in West Texas. While I am generally bearish on holding MLPs as long-term investments, I find Viper’s risk/reward attractive for the next year or two as its growth story plays out.

First, I need to apologize for writing about another MLP, as I do not like MLPs. Its just that every year or two, I do seem to find one that is relatively low risk with a meaningful reward such as last year’s PennTex Midstream Partners. So onward I go, but first I feel compelled to rehash some of the structural problems with MLPs.

Once upon a time, MLPs used to only own long-life, irreplaceable assets like interstate pipelines operated under long-term take or pay contracts with significant tax shielding depreciation that easily exceeded the pipeline’s maintenance requirements. This was all done under a partnership structure to avoid corporate income tax. Even better, unlike a fixed bond, classic MLPs held the potential for increased distributions over time as pipeline contracts are adjusted for inflation. Additionally, the nature of a pipeline system also provides opportunities for increased throughput and extensions. Yes, those were the good old days, back when MLPs owned real assets, and you could safely buy and hold.

Of course, MLPs were never really that great. Unlike the owners of common stock, limited partners in a MLP, own “units” not “shares” and have no shareholder rights at all. You must never forget that the “L” in MLP stands for limited. MLPs are not accountable to unitholders, but are managed by the general partner who holds all the cards and often collects excessive incentive fees at the limited partners expense. As a limited partner, you truly have no say in any matters of significance – honest, its says as much about 20 times in the 10-K. Don’t wait for an activist investor to show up and rescue you in an MLP, that’s not going to happen. There simply is no such thing as an activist limited partner. You just own “units” which are entitled to a proportional share of the available cash should the general partner care to distribute it, but you do not own a proportional share of the company.

Furthermore, owning an MLP with assets in 20-30 states means you pick up the responsibility to potentially file state income taxes in 20-30 states each spring. Did I say spring? I meant to say summer because you will likely get your K-1 forms late, so you will need to extend your filing date.

And what exactly does your partnership own? Does it possess an irreplaceable asset like the Colonial Pipeline running from Houston to New Jersey with dual 40” pipes buried in no longer obtainable right of way or do you have an asset that like an oil well that simultaneously reduces its reserves by one barrel for every barrel of oil it produces?

Its these later MLPs which own wasting assets that are most problematic. I wouldn’t say Ponzi scheme, at least in front of a lawyer, but I would say that when an MLP has to continually replace wasting assets with new assets, trouble eventually ensues somewhere down the line. Usually, the process is manageable at the beginning when the MLP is new, but it is as its asset base grows ever larger, the trick is harder to pull off. I am reminded of the circus act with the spinning plates, and even the best talent can’t keep all the plates spinning forever (See: Kinder Morgan dividend cut).

Lastly, you are buying an income producing asset whose price is intrinsically tied to interest rates, and the last time I checked, interest rates are inching up. Yes, its a real slow increase, but it’s upwards all the same, and investing, like sailing, is a lot more fun with the wind at your back.

But of course, it is precisely the hated qualities that create the opportunity. It’s the MLP’s tax restrictions which limit their ownership to individuals and away from large institutions. It’s their low liquidity which effectively prohibits large firms from buying the undervalued units while also exaggerating the downside effect of the occasional large sales that do occur. Or the tax filling challenges themselves probably lead many folks to say never again after they receive their first K-1, and the oddball nature of the sector further which can’t help but reduce investor awareness interest as well.

Combined, these problems reduce market efficiency and create mispricing for you and me. Sure, all things equal, I’d rather buy something without these issues, but many of my best purchases come not from buying what others don’t want to buy, but from buying what others would like to buy, but can’t for technical reasons.

So, let’s talk about why some of these technical issues that don’t apply to Venom Energy Partners. First, all of its assets are located in the state of Texas which doesn’t have a state income tax, so no special tax filing is required. True, the partnership may establish operations across the state line in New Mexico someday, but I can deal with one or two states’ filing requirements, its MLPs like Enterprise Partners with filing requirements in 35+ states that gives me nightmares.

Second, the general partner of Viper Energy does not charge an incentive distribution rights (IDR) management fee. To say this is unusual is an understatement, but it is came about because Venom Energy was primarily brought into existance to finance Diamondback Energy’s drilling program. By buying a royalty, Viper is effectively is buying part of Diamondback’s future production to fund Diamondback’s drilling program. This is similar to Taco Bell selling its physical stores to a real estate investment trust, leasing those stores back and using the freed up capital to build new ones. Oil wells, tacos, whatever; capital will find its highest use.

Currently Diamondback owns over 70% of the shares of Venom. Since Diamondback is still using Venom to raise funds, it is in Diamondback’s best interest to keep Viper’s expenses reasonable. Someday down the road, Diamondback’s interest in Viper will be much lower and the temptation to raise fees and turn Viper into a piggy bank will become irresistible, but we are a few years off from that for now.

Third, is that Diamondback’s CEO and CFO own just about as much Venom stock as they do Diamondback stock. Nothing gives me greater comfort than knowing that the CEO and CFO combined own over 20 million (one million shares @$20/share) reasons not to sacrifice Venom Energy Partners for the benefit of Diamondback.

Lastly, when I buy the occasional MLP, I strongly prefer ones that are trading down from their initial public offering (IPO) date for a couple reasons. For starters, I don’t want to pay the seven percent underwriter fees for the IPO and when the hype is the loudest. The best time is while they are still small enough to have a good runaway of accretive transactions. Many new MLP’s really do have reasonable growth plans at their start, its five to ten years later when the IDR fees become so large that trouble begins. Its then that the MLP can no longer make new acquisitions below the cost of its capital, growth stalls, investors demand higher yields further increasing the cost of capital, a vicious cycle begins the dividend gets cut and limited partners become bag holders.

Ok, that’s enough ragging on MLPs, it’s time to actually talk about what Viper actually does. Viper owns royalty interests in currently and future producing oil and gas wells in the Permian Basin of West Texas. Before an Exploration and Production (E&P) company like Diamondback Energy can drill a well, they must obtain lease rights to drills from the mineral right’s owners. In return, Diamondback pays a royalty to on all oil and gas production produced and sold. The royalty owner has no expenses other than taxes, no drilling costs or operating expenses. The royalty owner simply collects a check from the operator every month the well produces whether the operator makes money or not. Being a royalty owner is a definitely a good thing, but some people like don’t like to wait, so they sell their future royalties to third parties in exchange for a lump sum.

In fact, the only bad thing about being a royalty owner is that for every barrel of oil produced on your leasehold, the number of barrels left to be produced is, by definition, reduced by one. This is a little detail often overlooked by retail investors. You’ve really got to think of your distribution as part income, part return of capital because the asset you own isn’t going to produce forever.

Over the life of an oil well, its highest production is achieved on its first day. It declines rapidly at first and then more slowly, until many years later, the well produces less oil than it costs to operate it. At that point, the well is plugged and the royalty checks stop. Depending on the oil field, cumulative production in the first year or two could easily exceed all the production extracted over the next twenty. From the net present value perspective, getting your production back early is almost always economically advantageous. However, early paybacks also mean that if you don’t have a steady stream of new wells coming online, your royalty income will decline as your production naturally declines. Fortunately, for Viper, they have 250+ well sites left to be drilled compared to 786 wells currently in operation, which will push off the day of reckoning for a few years. In addition, their properties are in the Delaware and Midland Basins of West Texas where stacked plays are common. This means that there may be several oil and gas reservoirs located vertically under a single surface location (think free option), though some of the lessor reservoirs may not be viable for drilling at current prices.

To keep feeding the MLP so future distributions can grow, new royalties need to be purchased to replace the depleting production from older wells. Currently, Viper is successfully doing this. Diamondback has enough dropdown candidates lined up for Viper to acquire that the next few years to keep production rising and distributions increasing. But will they able to continue growing from a larger asset base, ten years from now?

I don’t know and fortunately, it is not critical to my investment thesis. Simply put, I only want to own Viper in its early growth stage, when the partnership’s goals are more manageable. I leave the riskier long-term ownership to yield hog investors who don’t appreciate the challenges of growing a depleting asset. (See red queen problem).

Risks:

I own an asset with the plan to sell it before others who own it realize that it can’t grow forever. Yes, I know this means I am speculating more than I am investing, but I am doing so with my eyes wide open.

Oil Prices

Obviously, a drop in the price of oil would immediately translate into lower cash distributions just like an increase would raise them. But a royalty owner, unlike a producer, doesn’t get impacted as severly. A drop-in oil prices from $50 to $49/bbl, will reduce a royalty owner’s income by 2%, but for an E&P company with $40/bbl in operating expenses, the same one dollar drop in oil prices will result in a 20% reduction in net profit.

I expect oil prices to drift in their current range until a little more global inventory is worked off, a geopolitical event occurs, or we have a recession. If I only knew which scenario would happen first, I could make a much more accurate prediction! If you really do know what the price of oil will be next year, I suggest skipping the rest of this post, and suggest you just buy oil futures on the NY Mercantile instead.

Cutesy Tickers

My track record of owning companies with cute ticker names like VNOM and FANG is mixed. Sometimes it means the company is owned by a maverick with an independent streak, but other times it signals a promoter. I put FANG and Diamondback into the independent streak, but I still prefer boring names and dull tickers for reducing the odds of a getting snake-bit.

Lack of detailed information on the royalty terms and locations

The information in the Viper 10-K and investor presentations are summarized data. Limited partners will never know in detail what Viper owns and what the terms are for most of its leases. For instance, you’ll get a pretty map of where leases are located but it won’t tell you if that dot on the map represents a 1% royalty interest or 12.5%. Until the next 10-K, we lack updated reserve information for the most recent acquisitions.

At a certain point, you basically just have to trust the management which is easier to do when like Viper, management owns a meaningful stake. So far, I haven’t come across anything suspect in my research that would lead to doubt them, but I do think their investor materials are best read with a critical eye. For example, management compares Viper’s cash margins and operating expenses to 20 E&P companies in the Permian. Of course, Viper’s numbers kick butt – a royalty owner it doesn’t have any operating expenses besides taxes and management salaries, it would be a scandal if its margins weren’t higher.

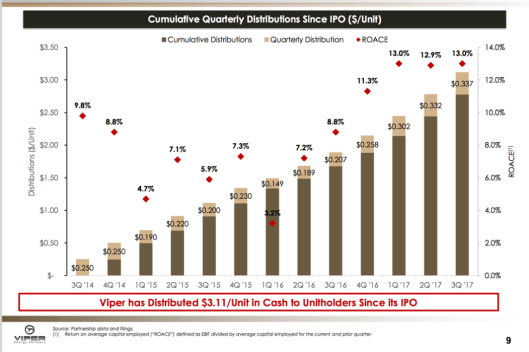

Or take a look at management’s presentation on distributions (below) and see the distributions going up in a nice smooth line. Of course, the distribution bars are always going up, they are plotting cumulative distributions!

Here is my look at the same quarterly distributions. In my chart, they still trend up, but the inherent volatility of owning mineral royalties is much more apparent.

In fairness, the company presented the actual quarterly numbers more reasonably in the “Significant Future Growth Trajectory” slide.

This slide highlights the short-term opportunity for me, but also the long-term risk. Viper has royalty positions on enough undrilled property and likely dropdown acquisitions to realize these projections in the near term, but what happens 5-10 years from now? Where will the production come from to replace the production lost as the wells deplete over time? As production increases, so does the amount of oil that needs to be replaced from depletion. The challenge just gets harder as the asset base gets bigger. Eventually, the gap can’t be filled, growth slows or reverses, distributions get cut and the limited partners find themselves holding a declining asset.

Competitors

Blackstone Minerals (BSM) operates in the same oil and gas minerals royalty space and yields roughly the same but is diversified across many more geographies. While diversification is usually a good thing, I prefer the much narrow scope of Viper in the Permian Basin where break-even costs are lower for E&P companies. One of the risks of holding an oil lease royalty is that your E&P operator will chose to drill wells elsewhere rather than on your property. Since, drilling for oil in the Permian is more profitable than anywhere else in the U.S. right now, I prefer keeping all my eggs in the prettiest basket.

When to buy:

Well a couple weeks ago would have been good, like back when I started writing the post, but don’t worry, you will probably have another opportunity to buy lower in the future as well. MLPs raise capital to fund acquisitions by selling new shares. (My hate of dilution is one more reason not to buy a MLP). To sell these large blocks of new stock, Viper will have to offer a 10-15% discount to the current stock price to attract large institutional buyers. Some of these buyers will then turn around and flip the shares for a quick buck. By all means, if you suspect a secondary offering is being planned, wait to buy until the price drops on the news.

When to sell:

A great reason to sell an investment held by yield seekers is when the future gets murky. Should Diamondback slow down its land acquisitions and drilling, Viper’s most visible growth path would slow down as well. Another reason to sell is when the asset base gets significantly larger and growth becomes mathematically challenging. Currently, Viper has a market cap of 2.5 billion. I will likely sell around a 3.5-4.5 billion market cap because I want to be out of the company before it becomes difficult to find enough future acquisitions at attractive prices to feed the growth beast. Until then, I like the risk/reward.